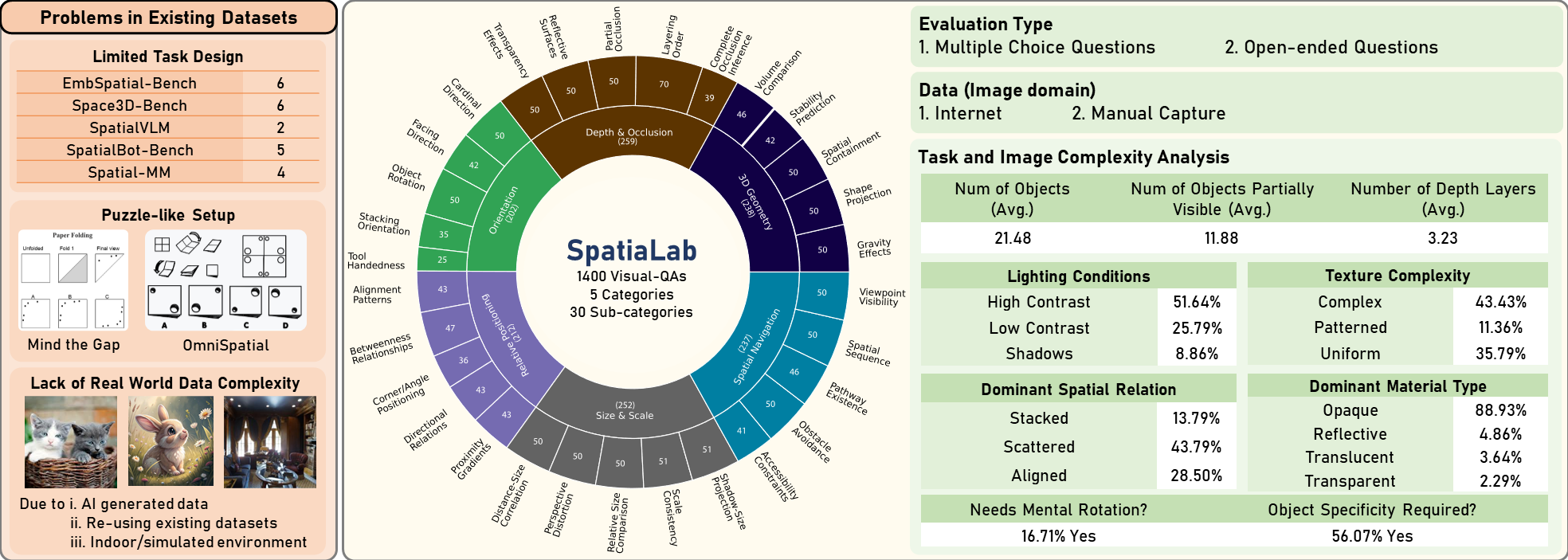

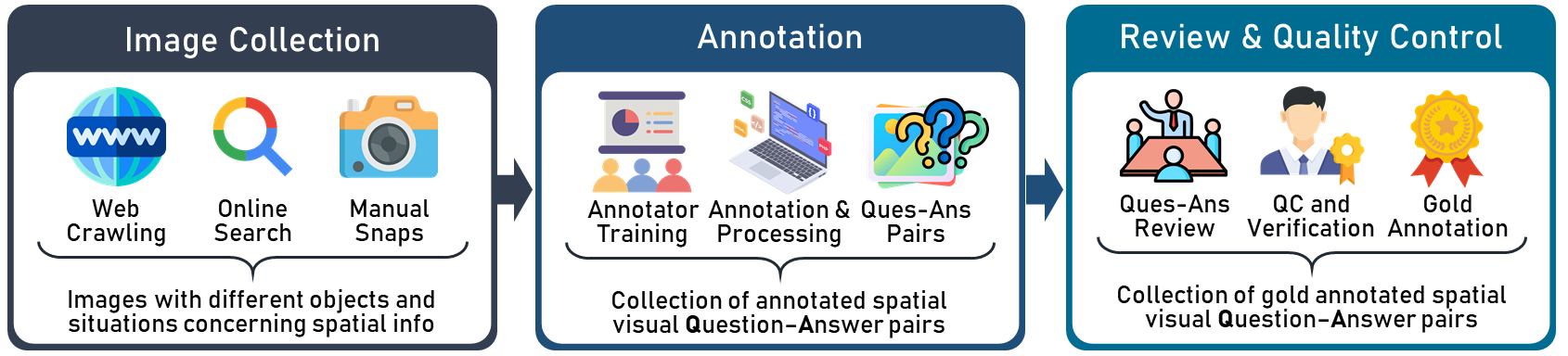

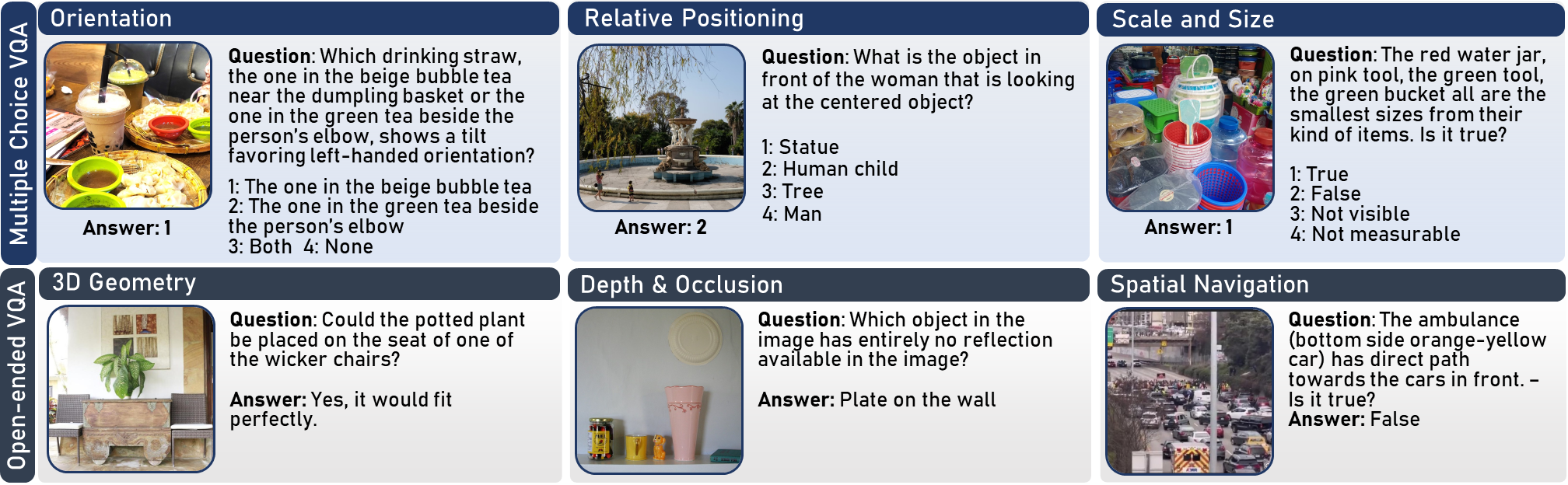

SpatiaLab: Can Vision–Language Models Perform Spatial Reasoning in the Wild?

Computational Intelligence and Operations Laboratory (CIOL) • Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST) • Monash University • Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI)

Accepted to The Fourteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2026)

📄 OpenReview 📄 arXiv 🤗 Hugging Face 🤗 HF (Paper) Kaggle GitHub